The rise of human trafficking

Social media helps lure in more victims

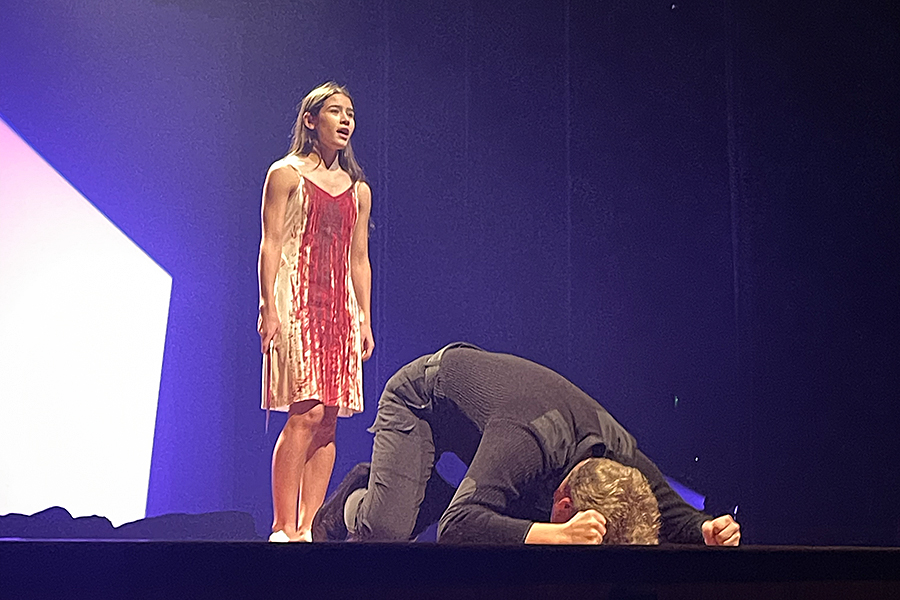

Comal Independent School District teachers watched human trafficking videos are part of their training.

October 6, 2021

“Don’t talk to strangers.”

It’s a phrase drilled into the minds of children as soon as they can walk. In elementary school, 6-year-olds learn not to hop into lone, white vans and that candy from strangers in trench coats is best avoided.

As the kids grow up, a variety of self-defense weapons stand at attention on the shelves of stores such as Academy and Walmart. By high school, most students can spot the sign in real life, but predators developed a new tactic that reaches teens easier through the “pocket-sized devices” they carry every day.

As the internet’s influence integrates further into social life, increasing online safety awareness combats against human trafficking by helping teens recognize red flags of predators.

“Human trafficking is all about exploitation,” student support specialist Lisa McGinnis said. “People tend to think of it as immigrants in a truck when really it’s about exploitation with a purpose.”

According to the Attorney General of Texas’ website, human trafficking involving minors includes any of the two instances: using children for commercial sex by any means and for labor by force, fraud, or coercion. Despite a common misconception, the term encompasses both victims transported and stationary. The majority of trafficking cases, at their most basic level, take root through manipulation tactics.

Thirty-eight miles down the road from Spring Branch, the San Marcos Police Department, aided by state authorities, arrested seven men operating a sex trafficking scheme in Hays County. By posing as minors online, female officers baited the perpetrators into leading authorities to their operations.

“Social media has allowed predators to cast a wider net,” McGinnis said. “Sexual exploitation online is what we really miss and what we’re really concerned about.”

Gov. Greg Abbott created the Child Sex Trafficking team to help protect victims, recognize the signs of sexual exploitation, help victims recover and heal and bring justice to traffickers.

“Texas’ Child Sex Trafficking Team has implemented a number of statewide initiatives to help bring an end to the horrendous practice of child sexual exploitation,” Abbott states on the website, “but we still have much work to do.”

Socioeconomic factors such as poverty, substance abuse and nationality status all serve as vulnerability risks. Predators also might take advantage of mental health and low self-esteem as a way to get a foot in the door and gain trust.

“LGBT+ and teenagers, especially online, are particularly at risk,” McGinnis said, “any marginalized group — anyone who feels like they can’t reach out.”

As social media increases its influence, lines blur between genuine connection and manipulation online. Without hearing someone’s voice and facial expressions, tones are harder to interpret, and red flags are easier to explain away. Dismissing an uncomfortable feeling is as simple as deleting a message, and sending an explicit picture is easier than arriving at a prearranged meeting place.

Predators seek out the loose threads and insecurities of teenagers to use as leverage. Typical red flags include asking for pictures and personal information, particularly location and home life situations. Predators play on emotions of guilt and shame by asking to exchange explicit photos and then threatening to leak them out if victims don’t continue to supply more. From there, teenagers become hooked and fear exposure too much to report their abusers.

“It starts with ‘send a pic of your face,’ ‘send a pic of your smile,’ and it just spirals from there,” McGinnis said. “It’s not going to start with the big questions.”

Accountability and awareness serve as strategies to prevent situations from spiraling. A trusted adult or older confidant provides a voice of reason removed from the situation to support victims and help designate what to do. Over the summer, Comal Independent School District teachers watched educational videos and presentation on how to identify instances of abuse and report suspected cases in the classroom.

“Our job as adults is to be aware of what our kids are doing online,” McGinnis said. “Parents should know it could happen to anyone, even if they’re smart, even if they’re savvy.”

Those who suspect themselves or someone they know to be potential victims of human trafficking can call the National Human Trafficking Hotline at 1-888-373-7888 or text “Help” or “Info” to 233722.

“Trust your gut,” McGinnis said. “If something feels off and odd, it probably is.”